Election Tracker: Hungary Parliamentary Elections 2026

Follow the trends and forecasts for the 2026 Hungarian elections with us.

Well it’s 7 months until the parliamentary elections in Hungary, which means that we are soon reaching the most intense campaigning period. Polling will pick up as well, and instead of seeing a handful of reports over a quarter, we’ll probably get that many in a month, which will enhance the overall accuracy of both the aggregating model and the seat allocation simulations.

A Quick Recap

Some background information of the Hungarian electoral system for international readers. The parliament consists of 199 seats, of which 106 are won in individual First-Past-The-Post (FPTP, akin to the US or UK and similar systems) electoral districts. 93 seats are allocated via the ‘national lists’ - the threshold of which is 5% vote share, then proportionally distributed using the d’Hondt method, with minority representatives having a preferential quota.

A unique Hungarian twist is the concept of ‘fractional votes’: this is used to assign extra votes to a party’s national list based on the amount of votes in each FPTP district. This is is a bit of a complicated system with two different components, but the gist of it is:

the ‘loser compensation’: all parties who reached the parliamentary threshold are assigned extra votes to their national list based on their candidates who didn’t win in FPTP districts

the ‘winner compensation’: these fractional votes are awarded based on the margin of the winner ahead of the 2nd placed candidate (minus one) and adding all votes cast on candidates who lost (so if they won by 10k votes in a district, they get 9.999 extra for the national list).

This is sadly not simulated in our model as this escapes our current capacities but our assumption is that this would have negligible effect anyway and the toss-up seats abstract these post hoc changes adequately for now.

The parties on the ballot include Fidesz, the governing party since 2010 (and having a 2/3 supermajority for almost the entire time); DK, started by a former prime minister and having a track record of participating since 2014; MH the offshoot of the 2018 runner-up, split from them before the 2022 election; and MKKP, a sort of ‘pirate-party’.

The last few months, and years even, were already turbulent on the Hungarian political landscape (more so than usual) with the emergence of the TISZA party in early 2024, a new(ish) center-right formation led by Péter Magyar (formerly related to the current system).

There are a bunch of other smaller parties too but they scarcely stand a chance of having measurable support so we’ll skip them from the introduction.

Vote Share Over Time

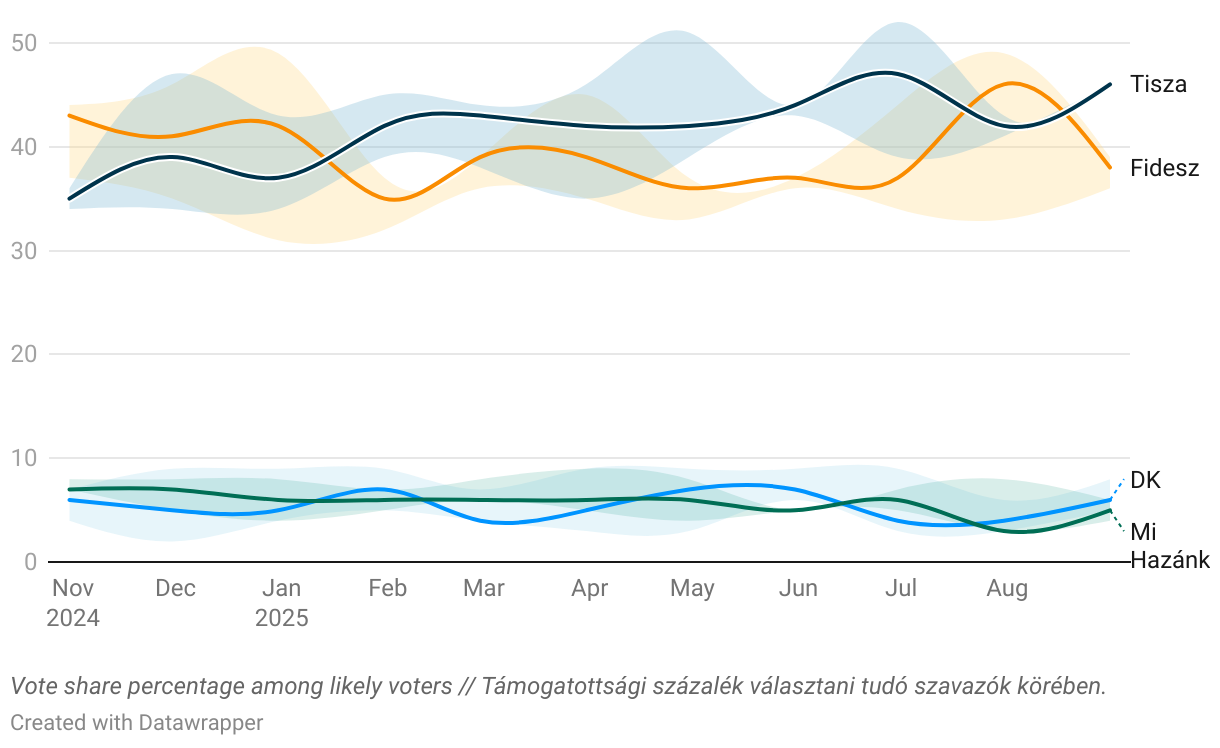

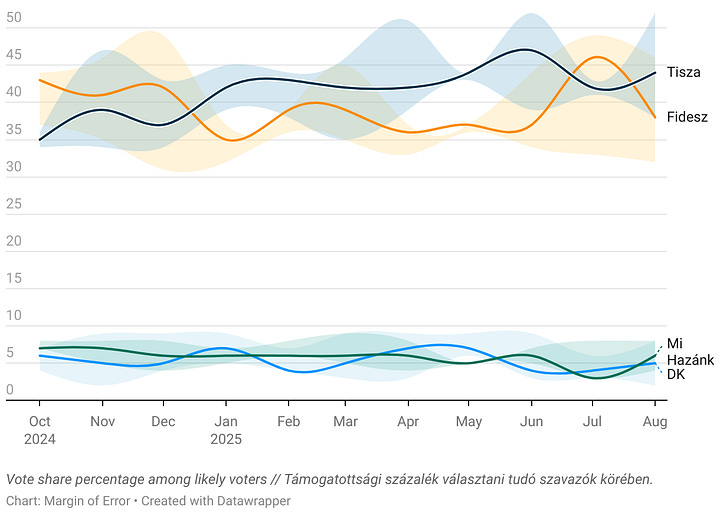

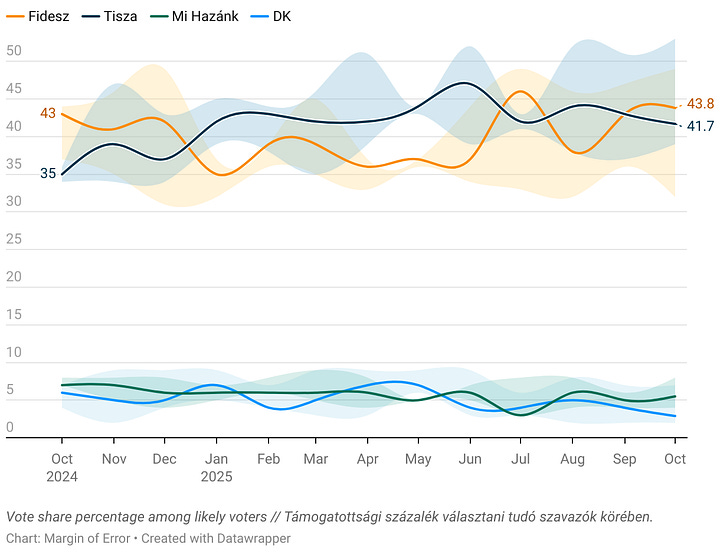

By this point in time TISZA (in red) overtook Fidesz (orange) in most polls, but as we can see here, it is far from a race over:

The confidence bands also show a huge distribution of measured support for Fidesz, with a staggering 13% possible difference between highs and lows! Interestingly though, the support for TISZA seems to be gauged much more narrowly with fluctuations being only within the margin of error. We also have to note that the sudden shift in tendencies so far might be a mirage as July has only really seen what we deemed as low quality polls - we’ll see whose lead holds as the August polls are coming in, but we shouldn’t be surprised if a reversal is solidified sooner rather than later.

These swings partly depend on the pollsters perhaps skewing for one side or another as they are often sponsored by the parties, and partly due to a perceived trust in these institutions and the government itself, but our model works hard to normalize the resulting uncertainties beyond simply averaging them out.

We can also observe a slow but steady downward trend for the other two tracked parties as they edge the parliamentary threshold, creating a nonzero chance of them not winning any seats from the proportionally allocated national list. Due to the nature of the FPTP seats, it’s almost guaranteed that only TISZA and Fidesz will win electoral districts which means there is a real possibility of having only these two parties sitting in the parliament for the next cycle. Considering that these two parties are practically diametrically opposed (not to mention the rigid government-opposition divide in Hungary), coalition building seems off the table based on conventional wisdom; and a hung parliament is also not out of the question (see below for very preliminary seat projections)

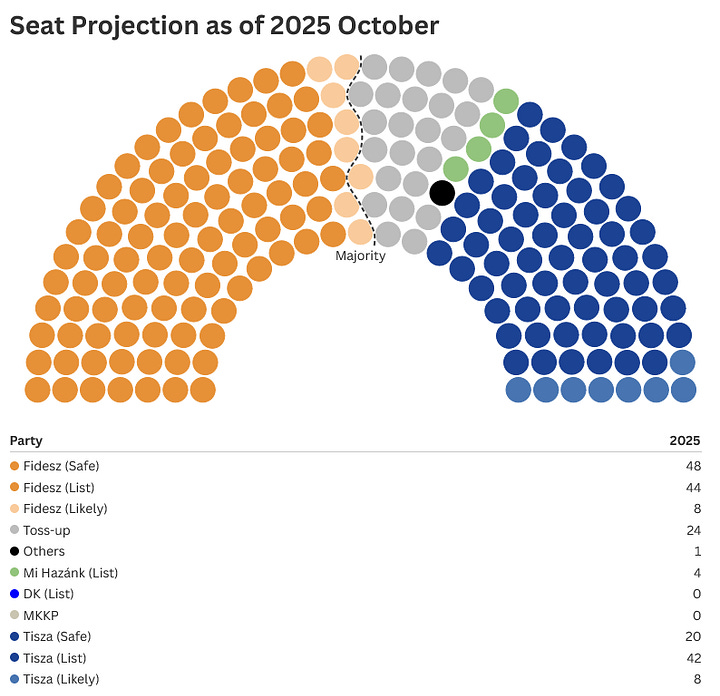

Simulating The Parliamentary Seat Allocation

We also built our first simulation model tweaking it to Hungary-specific rules and challenges. At it’s core, the simulation is a Monte Carlo test designed to simulate 10.000 elections every time it’s ran. Each of these 10,000 'elections' uses slightly different, but plausible, (defined by thresholds supported by historical trends, such as high and low turnouts being based on historical elections) combinations. By simulating these variations capturing a full spectrum of possibilities. These variables include:

Shifting turnouts; how many undecided voters might participate and how they could do so; and random deviations within the margin of error.

For the August data, we simulated undecideds as 28-35% of the full electorate (based on polling trends and adding a margin of error for some wiggle room) and ~70% turnout rate. This could change as new polls narrow the undecided share more.National party list seats based on our adjusted national vote share from above. While the nuance of the ‘fractional votes’ are not directly simulated due to our limitations, we believe that the simulation’s broader approach accounts for its effects indirectly with elements such as the shifts above and the clear uncertainties of the toss-up seats.

FPTP districts are simulated individually, adjusted by factors such as a proportional voting support shift based on the 2022 election results and the current adjusted vote share, the final result in 2022 in each district and small unpredictable local swings. This is perhaps the most challenging and rough part of the simulation as district level polling is not readily available. Nevertheless, the local dynamics we are working with here still offer us the opportunity to predict possible outcomes. Based on the simulation results the seats are categorized ‘safe’ (a clear win with a comfortable margin), ‘likely’ (a close win which still could realistically flip), and ‘toss up’ which is everything else that are too close to call. There are also 4 new districts created first debuting in 2026, which we categorized as toss-up without further simulating them due to lack of historical data and we wouldn’t be confident including more workarounds.

This gives us a valuable estimate of how the parliamentary composition could look like, without veering into the territory of ‘reading tea leaves’ trying to predict unpredictable shifts.

We will follow the events and the data of this election closely and you can expect shorter monthly check-ins when we update our charts including this one above; but if you’d like to check out our full data and latest projection in an interactive format, visit our Github here.

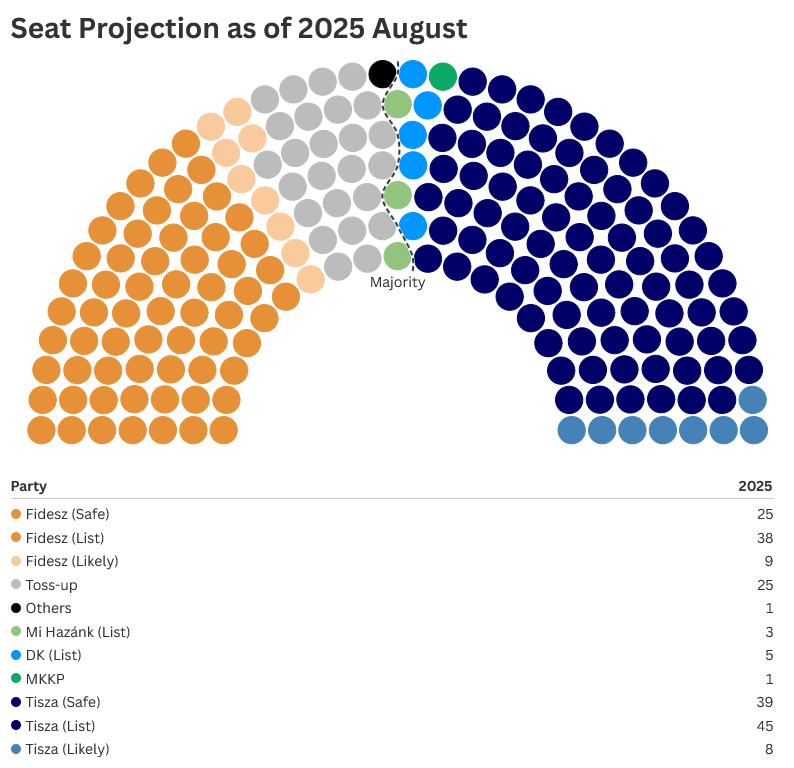

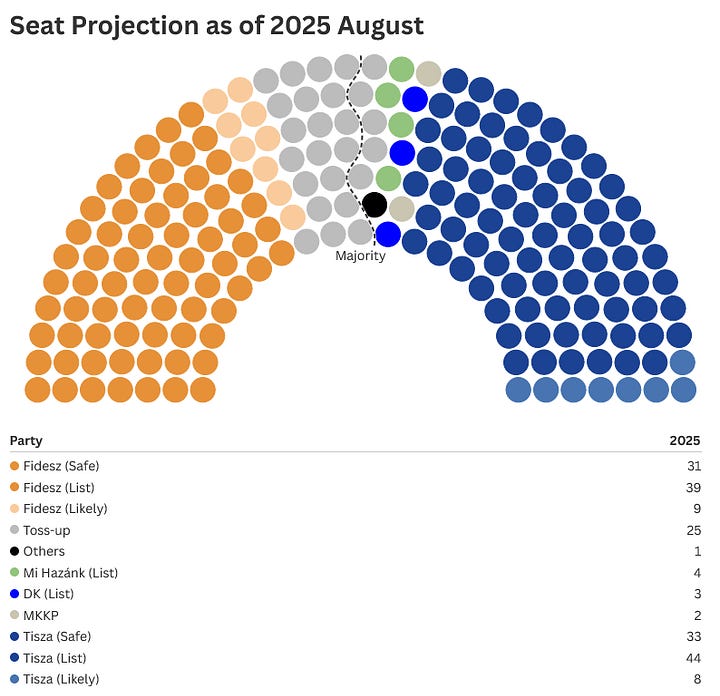

2025 End of August update

Seems like the July reversal didn’t hold at least for now, which is not entirely surprising given how tight the race is between the top 2 parties (and how far the election date still is). The party Tisza regained its lead at the moment and stably hovers slightly above 40% support, while the vote share of Fidesz is doing parkour over the last 3 months (note the 8% difference between July and August).

A lead in vote share however doesn’t automatically mean a commanding lead in parliamentary seats, especially in the Hungarian election system and we can see on the new projection just how slim this margin would be (the simulation is also less impressionable than the aggregation model).

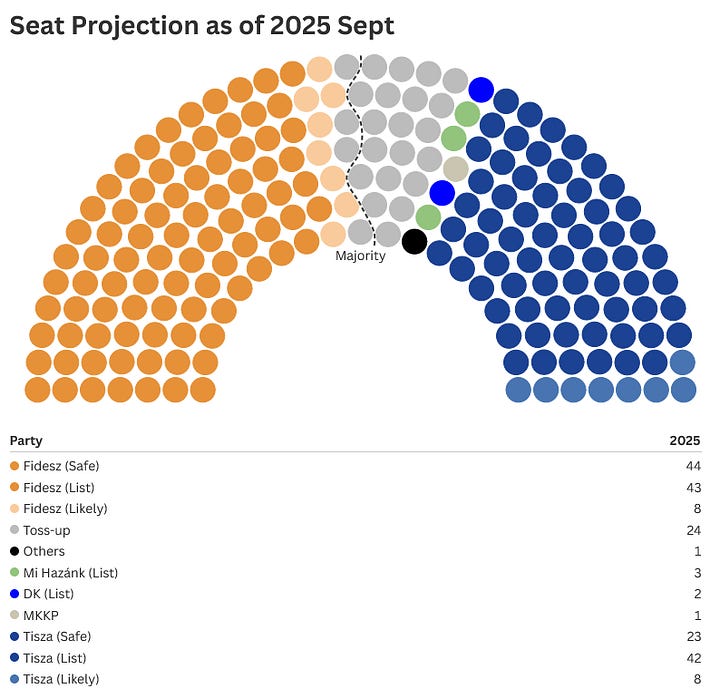

2025 September Update

The flip-flopping of the polls continued, though in September a new pollster, McLaughlin & Associates, entered the landscape without previous presence in Hungary. While the individual poll doesn’t matter much, it is putting our model to work as it has to place it without historical accuracy data. Our opinion is that we’d rather risk overweighting a new pollster than dismissing them just because they haven’t polled this electorate yet. As such we’ll see how the charts change in October when it’s more likely that only established firms publish polls.

2025 October Update

October Hungary 2026 election tracker update time! Currently our only active tracker by the way.

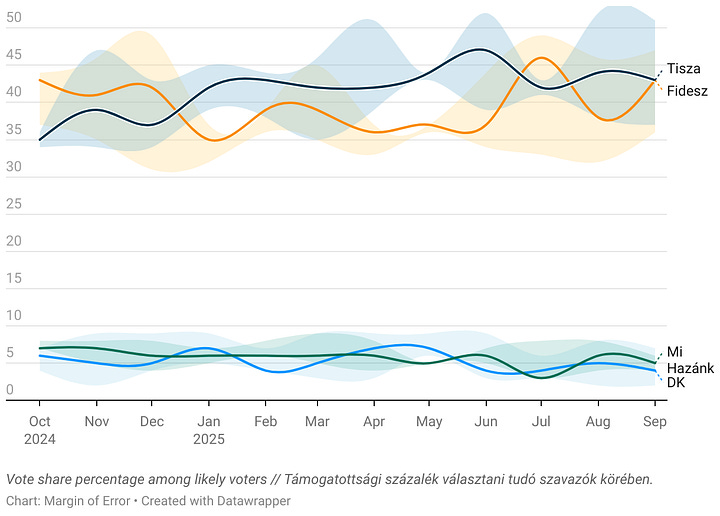

At this point I won’t even call out how much the polled numbers top 2 parties can change month-by-month - it seems we are stuck with this double helix of a chart.

This is partly because of the stark difference between government and non-government aligned polling firms. We don’t specify which is which because our model doesn’t factor in bias for weighting, only rolling accuracy. Now of course in past cycles government-aligned pollsters were more accurate generally (not going to unpack that) so at some point it’s entirely possible that they will miss the mark and thus the aggregation will also be off in the end. Just something to keep in mind.

While we don’t care about alignment generally we also made a choice in excluding a firm, called XXI. Század (21st Century) without previous track record which is way too openly and closely aligned with the governing party. We felt that we couldn’t yet give it the benefit of the doubt and as such treat them the same as any other newcomer, essentially giving them an average rating above established but historically lower quality firms. This is because of the past of the head of the firm - we stand by our choice and may reconsider next time.

2025 October Update

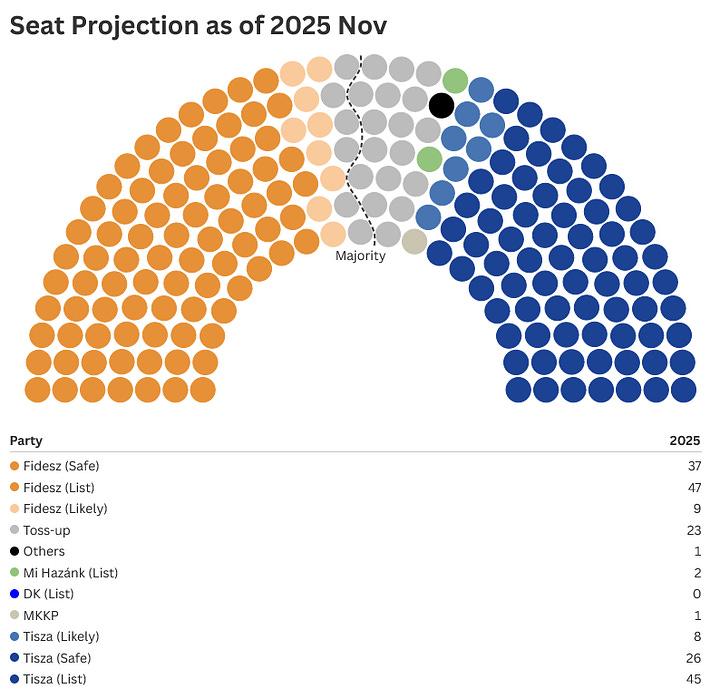

In our last update in 2025, let’s take a short look at the November polls. Probably at this point to no-one’s surprise TISZA took the lead again in the overall adjusted average. As we can see, the race is not any less close; in fact after these position switches the two biggest parties keep staying closer to each other. The other two properly measurable parties are also slipping below the parliamentary threshold, though that doesn’t mean they can’t get there.

There were also new polling firms publishing their snapshots over the course of the last few months, we’ll see how many will continue to do so.